Why Bourbon Will Survive the Market Retraction (Again)

History Repeats itself

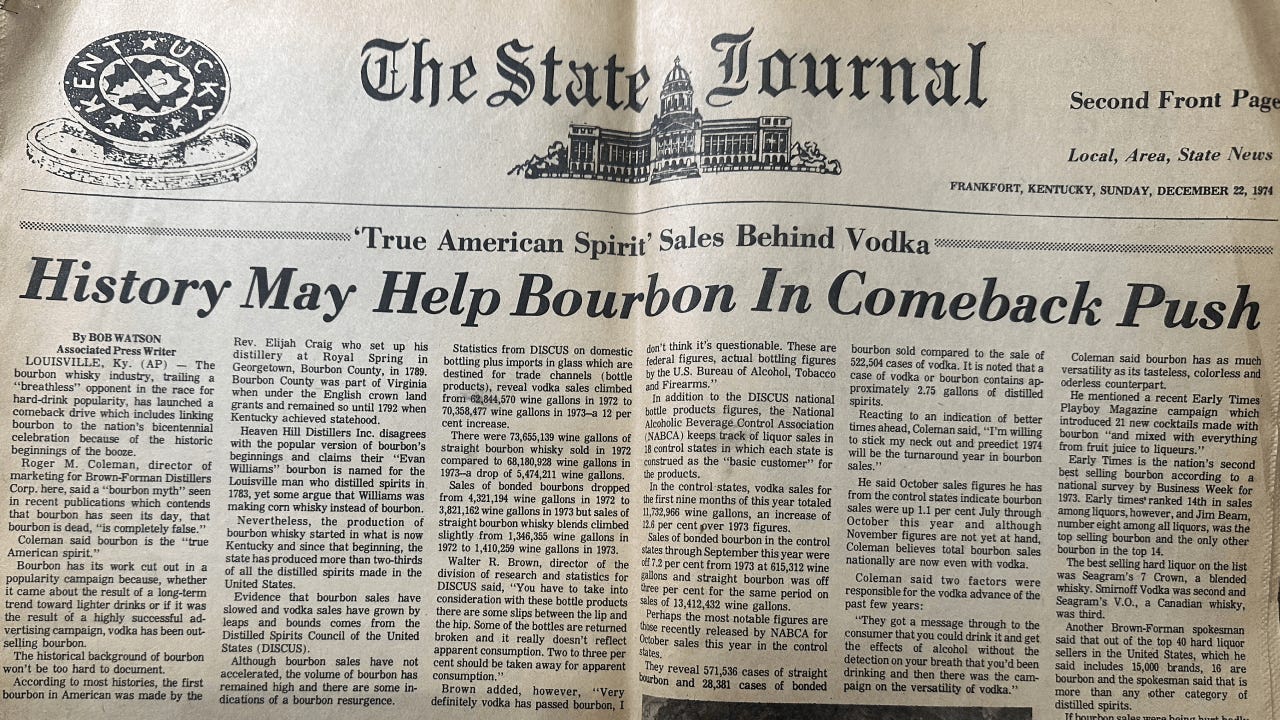

A coworker walked into my office last week holding an old newspaper his dad had saved. He’d been going through boxes trying to figure out what his dad thought was worth keeping, and he found this article from December 22, 1974—The State Journal out of Frankfort, Kentucky. Headline: “History May Help Bourbon In Comeback Push.”

I immediately brought it back to my desk and started reading through the faded newsprint, it felt like reading today’s trade publications. Just different names and dates.

The bourbon industry in 1974 was worried. Vodka was taking over. Industry people were defending bourbon’s versatility, its heritage, its authenticity. They kept pointing to inventory levels and this “true American spirit” designation like it was going to save them. One guy insisted people would eventually realize that “drinking this 80-proof alcohol is not as good as this bourbon.”

Fifty years later, bourbon’s in almost the exact same position. Except now it’s not vodka. It’s tequila and RTD cocktails and lions and tigers and bears….oh my.

The Current Reality

Younger consumers are moving toward lower-proof spirits, tequila, and ready-to-drink options or just not drinking at all. Those ultra-premium bourbon bottles sitting between $80-$250? They’re not moving like they used to. Price fatigue is real.

And the industry’s response? Same playbook as 1974: versatility, heritage, authenticity.

Tom Godfrey from FOCO in Barcelona told Punch: “Bourbon is a spirit that we think is one of the most versatile to mix with. If the drink is stirred, shaken or thrown, carbonated and served tall, or even blended, bourbon plays so well with so many fresh ingredients.”

That’s basically what they were saying about competing with vodka in ‘74.

What’s Actually Different This Time

HOWEVER. Bourbon’s position now is fundamentally different from 1974 in ways that actually matter:

The infrastructure is built. In 1974, they were still recovering from Prohibition. Now there are 12.6 million barrels aging in Kentucky warehouses. The Kentucky Bourbon Trail brought in 2.5 million visitors in 2024, generating over $400 million in tourism revenue. The industry supports 23,300 jobs and delivers $9.2 billion in economic impact. This isn’t a dying category scrambling for relevance. It’s a mature economic engine recalibrating.

Premium positioning is already won. Tequila and RTDs are still fighting to establish premium credibility. Some reposado sales are growing, sure, and some RTDs position as “bar-quality,” but bourbon already owns the premium American spirits space. High-end and super-premium bourbon sales grew 18% in 2024. When consumers trade up, they’re going deeper into bourbon, not leaving it.

The craft diversity. 1974 was dominated by a handful of large producers. Now there are over 100 distilleries in Kentucky alone. Craft operations are experimenting with heirloom grains like Bloody Butcher and Blue Clarage, innovative barrel finishes, sustainability practices that actually resonate with younger consumers. Charlie McCarthy from WSET notes that the variety in bourbon from char levels to barrel placement “makes bourbon an ideal spirit for mixing.” This diversity didn’t exist in ‘74.

The competition’s structural weakness. IWSR research shows consumers regularly can’t identify whether they’re drinking a malt-based or spirit-based RTD. The category is built on convenience and marketing, not loyalty to the spirit itself. Tequila’s riding a wave of celebrity endorsements and trend-driven consumption. When that cools—and it will—what’s holding it up?

Bourbon has something neither can replicate quickly: decades of aging inventory that can’t be rushed, a defined geographic identity, and a production method codified in law.

“Bourbon 3.0” positioning. The industry is entering what analysts call “Bourbon 3.0”—deeper consumer education, enhanced brand experiences, global sophistication. The Bourbon Flight summarized it well: “The focus is no longer just on what’s in the glass, but on who made it, how it was aged, and why it matters.”

Smart positioning. RTDs compete on convenience, tequila competes on trendiness. Bourbon’s doubling down on craft, story, and experience—the things that create lasting brand loyalty.

What Actually Kept Bourbon Alive

Bourbon’s survival during the vodka era came down to a combination of desperation and opportunism. Export markets (i.e. Japan) became a critical revenue source. Wild Turkey’s Eddie Russell put it bluntly: “Japan was a savior for us,” absorbing hundreds of cases when American demand had collapsed. Innovators like Elmer T. Lee (Blanton’s Single Barrel, 1984) and Booker Noe (Booker’s, 1987) created the premium single-barrel and small-batch categories, proving bourbon could command higher prices if positioned as craft rather than commodity. But distilleries also survived by keeping bottom-shelf brands alive, often dumping well-aged inventory into cheap bottles just to move product and generate cash flow. By 1980, Kentucky distilleries were making less than 1 million barrels per year but sitting on 5 million barrels of aging inventory. That meant bottom-shelf bourbon in the 1980s frequently contained older whiskey than many premium bottles today—not because distillers were being generous, but because they were desperate to monetize aging stock that wasn’t selling. The industry didn’t survive through quality focus alone; it survived through export hustle, premium innovation, and sometimes just selling really old bourbon really cheap to anyone who’d buy it.

What 1974 Actually Teaches Us

Bourbon survived vodka’s dominance by being unapologetically itself. The industry waited out the trend, maintained quality, and was ready when consumer tastes evolved back toward flavor and complexity.

Today’s playbook, better tools: tourism infrastructure, craft innovation, global distribution, and a generation educated by craft cocktail culture to appreciate what makes bourbon special.

Reid Mitenbuler captured it: “Bourbon refuses to be rushed—drinking it is an exercise in slow sipping, just letting the concentrated bursts of honey, spice, and vanilla flavors unwind on your tongue.”

You can’t rush aging bourbon. You can’t rush building a distillery. You can’t rush creating heritage.

But you can rush a hard seltzer to market, slap a celebrity name on tequila, or reformulate an RTD when sales slow.

The Generational Shift That Tells the Whole Story

I think the least surprising thing about the article is the tone. It was defensive, almost precious about how bourbon should be consumed. The final quote was essentially: don’t ruin bourbon by mixing it with too much cola and sugary stuff—you might as well drink vodka.

That was Booker Noe’s era. Bourbon purists defending the spirit from being bastardized. Maybe the greater population has evolved past this but not all. What do you think happens every time someone new to the segment uses the word smooth or makes a cocktail with the wrong “premium” whiskey?

Flash forward to 2025, and Fred Noe—Booker’s son, Jim Beam’s seventh generation master distiller—has this to say about how to enjoy bourbon: “Drink it any damn way you please.”

That shift tells you everything about why bourbon’s positioned differently now. In 1974, the industry was rigid, trying to hold the line on tradition while losing market share to a more flexible competitor. Now? They’ve figured out you can honor heritage while meeting consumers where they are.

The infrastructure, the premium positioning, the craft diversity—those all matter. But the real competitive advantage is that bourbon learned not to be precious about itself while maintaining what makes it special.

Bottom Line

After years of explosive growth that brought speculators, flippers, and casual drinkers into the category, bourbon’s returning to a smallerish audience. The explosive growth brought some new folks to the fold but many of them are tired. Ready to try something new.

In 1974, bourbon was defending itself against a spirit with no taste, no color, and no history. In 2024, it’s defending itself against convenience and celebrity and maybe exhaustion.

Fifty years ago, the industry said bourbon would survive because of its heritage and authenticity. They were right then. They’re right now.

The main difference? This time they’ve got the infrastructure and positioning to actually capitalize on it when the market corrects. And they’re not going to lose share by being inflexible about how people should enjoy it.

Which, looking at what happened with vodka, might be the lesson that actually matters.

I’ve included photos of the original 1974 clipping below. The parallels are striking, and the contrast between then and now is probably more instructive than the similarities.